Introduction

The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali are one of the most important texts in all of Yoga. The text comprises 195 verses divided into 4 parts. It provides a deep and complete understanding of the process of Yoga. It describes Yoga, ways to practice it, the hurdles that can come, their solutions, and the eventual results. Not only does Patanjali describe the processes of Yoga but also provides an insightful view on the philosophy of the soul, God, and salvation.

This blog outlines the Yoga sutras of Patanjali, highlighting the key points and explaining what they mean. Whether you’re a beginner or an experienced yogi, this is an essential text that you need to read!

What is Yoga?

Yoga is a practice that has been around for centuries and dates back to the time of the Vedic era. It literally translates to ‘confluence’ or ‘conjunction’ and we believe it to be the way to bring the two worlds of materialism and spirituality together.

Patanjali defines it as, “Blocking the segmentations of consciousness is Yoga”. (Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, 1.2)

The mind or consciousness, or awareness sprouts into several segments, creating a variety of thoughts, desires, emotions, and activities. Yoga is the practice to stop all those activities and return to the original form of the soul that is undivided and ever-calm. With its mastery, a person can merge their soul into the universal one and attain salvation while living. Living salvation is the state where a person, although performs actions, their actions do not lead to any consequences. Hence, they are not born again in the material world because of their sins and virtues. Also, while living, the feelings of pain, pleasure, or any other emotions do not hinder such people, as they are in a continuous meditation of the soul.

To achieve such a state, there are several disciplines of Yoga, each one imparting wisdom uniquely. However, we will focus on the discipline that was started by Patanjali.

What are the benefits of Yoga?

Yoga is a physical and mental practice that joins the conscious and the unconscious aspects of a human life. A good session of Yoga is certainly relaxing and provides for a pleasant hobby, but it has many more benefits. Yoga activates your frontal cortex and also helps increase the good hormone flow, resulting in reduced stress, anxiety, better decision-making, thinking skills, increased creativity and many more.

Asana and Pranayama have a variety of health benefits, such as better breathing control, improved sleep quality, decreased depression symptoms, increased energy levels, etc. Only within a few days of practicing Asana and Pranayama, you will start feeling more energetic, your hunger will increase, and you will start living a balanced life.

However, you can benefit from these advantages even following the modern disciplines. What makes Yoga unique is its ultimate purpose. People believe that life is larger than the material world. They accept that the spiritual world completes the inquiry of the material universe. And so, Yoga becomes a tool for such people to explore that side and hopefully attain a level of salvation where the body becomes discardable and what remains is only the soul.

What are the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali?

Yoga originated in India. One of its key practitioners, Patanjali, is the most popular name we hear in the modern world when we think of Yoga, and I must add, not in vain. The Ashtanga Yoga Sutras of Patanjali are one of the oldest documents on the practice of Yoga, and they provide detailed and yet simple instructions for achieving spirituality.

Yoga exits in different forms, like Vinyasa Yoga, Hath Yoga, and others. Different sages have advised different ways of following it and hence have established their own unique disciplines. Some of them demand extreme physical penances, while others ask the yogi to live a tough life alone in a jungle. However, the sutras written by Patanjali can work for all kinds of people—the hermits and the people with families alike.

Patanjali has divided his sutras into four sections. Below is a brief introduction to each part.

Samadhi Pada

The first section, ‘Samadhi Pada’, contains 51 sutras. It describes what Samadhi (salvation) actually is. Patanjali describes salvation and its types, detachment, the problems one could face and their solutions, and the true form of God.

Sadhana Pada

The second section, ‘Sadhana Pada’, has 55 sutras about the how a beginner can start the practice. He also describes the eight limbs of Yoga and the results of Kriya Yoga (Yoga of activity) namely ill-knowledge, mental pain, etc. and their solutions. In the end, he describes Pranayama and Pratyahara briefly.

Vibhuti Pada

The third section, ‘Vibhuti Pada’, also has 55 sutras. In this section, he describes unique skills gained with Yoga, the limbs of Dharana, Dhyana, and Samadhi, and the importance of balance and its results.

Kaivalya Pada

The last section, ‘Kaivalya Pada’, comprises 34 sutras. In this section, sage Patanjali describes the state of ‘Kaivalya’ (a type of salvation), the ways to attain it, and its results. He also mentions the ways to attain the five skills, four actions, how actions lead to desires, and its solution.

To explain, each sutra is out of scope of this blog, as its purpose is to make you curious about the original text. However, it is highly advisable that you read the original texts at least once and figure out if it works for you. Below are the eight limbs of Yoga that are vital for anyone who wants to call himself/herself a ‘yogi’.

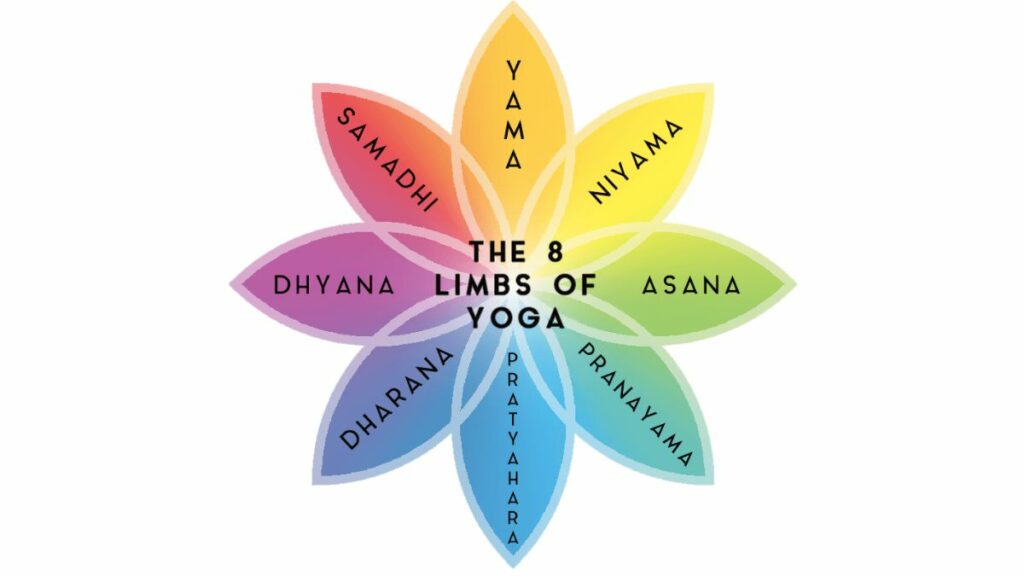

The 8 Limbs of Yoga

Although Patanjali has described the philosophy of life and its confluence with the supreme soul in great detail, his texts summarize that to remove the unwanted emotions, problems, and obstructions, one must follow what are called the eight limbs or disciplines of Yoga.

Patanjali says, “Yama, Niyama, Asana, Pranayama, Pratyahara, Dharana, Dhyana, and Samadhi are the eight limbs.” (Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, 2.29)

You can practice and try to master these disciplines separately or simultaneously. You can also choose to focus only on one limb and leave others for good. Patanjali and several other sages have said that even by mastering one limb of Yoga, liberation is possible. However, Patanjali has divided the eight limbs into two parts and has emphasized that practicing the last three limbs together is the best way to attain salvation.

He says, “Practicing the last three (Dharana, Dhyana, and Samadhi) together, focused on a singular object is called Sanyama (state of balance).” (Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, 3.4)

He also says, “The three limbs (Sanyama) work closer to attaining salvation than the former five (Yama, Niyama, Asana, Pranayama, and Pratyahara).” (Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, 3.6)

In conclusion, the limbs are not interdependent and do not have to be practiced in a certain order. However, it is best if you try them all in order if you have the ultimate aim of mastering spirituality through them. So, without further ado, let’s have a look at each one of them.

Yama

Yama is the first limb of Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras. It literally translates to restrictions. Patanjali describes its five types in his sutras.

He says, “Non-violence, truth, non-stealing, Brahman-conduct, and non-possessiveness are the Yama.” (Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, 2.30)

Non-violence

is to not hurt anyone with either mind, speech, or body.

Truth

is expressing, in the exact way as we witness something.

Non-stealing

is to not want, even in thoughts, to have what is of others.

Brahman-conduct

The sages have defined it as not having relations with women other than one’s wife, either with speech, body, or mind. With one’s wife too, one should have relations only in the mating season. For those who do not know what the mating season is for humans, different sages have defined it in different ways. Some advice that pre-winters are the mating season for humans, while some say that spring is. However, some sages have said that the mating season for humans is only when a woman is ovulating, and a person establishes the relationship only with the aim of childbirth.

Non-possessiveness

is the understanding that all material things, including one’s body, do not truly belong to anyone. The soul takes the seed from the father, womb from the mother, and after birth, as the body grows, it accumulates matter that was never its own. Also, at the time of death, it has to return all the elements back to earth, water, and so on. So, quitting the feeling of owning anything and believing that you are only temporary in this world is non-possessiveness.

Patanjali says, “These Yamas are the great austerities that are practiced irrespective of class, place, time, season, or any other rules and personal vows.” (Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, 2.31)

Upon mastering these Yamas, one realizes the truth of the world and lives a life that does not affect the future. The yogi does not create actions that lead to consequences. Following these habits, once the person dies, they are not reborn out of their sins or virtues and become liberated.

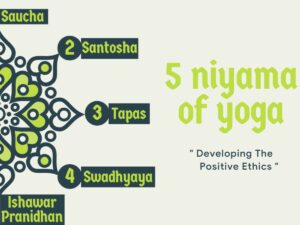

Niyama

Patanjali says, “Hygiene, contentment, penance, self-study, and devotion to God are the Niyama.” (Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, 2.32)

Hygiene

is the practice of cleansing the living vicinity, one’s body, as well as one’s mind and thoughts regularly.

Contentment

is to rid yourself of all desires of what is not and what could be. To feel satisfied and obliged with what one has is contentment.

Penance

has many forms. Performing actions that cause physical discomfort like fasting, tolerating extreme cold and heat, etc. are one type of penance. Another form is to only perform actions that are essential for survival (not enduring pain, and not having luxury) and dedicating all actions to God. Similarly, living in the society and following the rules (prescribed by the Vedas as Dharma) strictly according to class, place, position, and time is also a type of penance. In conclusion, it is a lifestyle that one chooses not to satisfy the body or the senses. Instead, dedicating all deeds to the service of the universe (considering humanity, animals, and even non-living things equal), or in the service of God (considering the entire universe false and as Maya) is penance.

Self-study

is the practice of reading philosophical texts and continuously thinking about them to find their meaning regarding oneself and the universe.

Devotion to God

is the belief that God is supreme. A person who is faithful understands that the world is an illusion, and the ultimate truth is the supreme soul that is eternal and formless. They heed the advice of the Vedas and the Upanishads. They live their life in a way of devoting their actions only to the welfare of beings, and do not add to the chaos because of ill knowledge. Ultimately, they leave the world as if they were never here.

Asana

According to sage Patanjali, “What is stable and pleasant is Asana”. (Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, 2.46)

Asana literally means the posture in which a person stands, sits, sleeps, etc. However, it has a different significance in practicing Yoga. Asana provides a stable position for the yogi to carry out the later steps of Yoga. If a yogi wants to meditate, or focus on their breathing, body, or a mantra, they should not feel distracted because of some unease in their body. Hence, mastering the discipline of Asana plays an important role.

Several sages, including Patanjali, have outlined several of these postures. To know more, if you look them up, you will find hundreds of them, but all sages have advised that the posture in which a person can stay for a long time without feeling discomfort, numbing of organs, or pain is the best asana.

Having said this, I should also say that if you are not sick, or do not have problems, try some of these poses, as they help us develop strength and flexibility in our body, as well as improve our posture. Also, they help with particular outcomes. For example, people who want to control their breathing and work with Kundalini should sit in Baddha Padmasana. Similarly, for chanting mantras, Mukta Padmasana and Ardha Padmasana are more appropriate. For people who cannot follow these difficult positions, they can sit or even lie down in any way they chose, and that position is called Sukhasana.

Pranayama

Patanjali says, “After mastering Asana, breathing in the air, exhaling it, and stopping its flow as per one’s capability is Pranayama.” (Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, 2.49)

Pranayama literally means controlling one’s breath. The Vedas have described the air as our life source. We breathe it in, and it travels to the entire body carried by blood. Then, the body uses that air to break down the nutrients, create energy, heal wounds, and perform several other bodily functions. This is basic science. However, the Vedas also say that with every breath, the body follows a rhythm (Breathing out sound ‘Ha’ and breathing in sound ‘Sa’, creates the continuous chanting of the mantra ‘Hansa’) and with that rhythm, the nerves (Nadi) perform lively activities. So, by controlling one’s breath, one can willfully control the nervous functions, resulting in activating or suppressing a body part, hormonal flow, or emotion.

According to the Upanishads, the main nerve is Sushumna (Spinal cord) that runs from the tailbone to the brain. Including 14 other important nerves like Ida, Pingala, and others, there are 72,000 nerves in the body. Also, the air that we breathe exists in our body in 10 forms, namely Prana, Apana, Vyana, Udana, Samana, and others. These life-sources travel inside of these nerves and handle all bodily actions like urges (hunger, excretion, reproduction, etc.), emotions (pleasure, pain, fear, etc.), functions (digestion, sleep, building, healing, etc.), and their imbalance results to diseases.

How to Practice

The sages have described Pranayama in three stages: Puraka or inhaling, Kumbhaka or stopping the breath, and Rechaka or exhaling. One should practice these steps with a time ratio of 1:4:2. There are different timings prescribed. For example, one consensus is that an inferior Pranayama takes a time equivalent of enunciating 12, 48, and 24 long verbs; mediocre Pranayama takes 24, 96, and 48 long verbs; while optimum Pranayama takes 32, 128, and 64 long verbs. But the consensus among most of the sages is that of 16, 64, and 32 long verbs.

The time taken to enunciate 16 long verbs is roughly 3 seconds. Hence, the standard practice for Pranayama should be to inhale in 3 seconds, stop breathing for 12 seconds, and then exhale in 6 seconds. The texts also advise that one should increase the time for Kumbhaka (stopping) gradually, as much as possible, until the yogi stops inhaling and exhaling, and permanently stops their breath. Leaving the body thus, a person can achieve salvation.

It is important to remember that with Pranayama; the yogi controls how the life flows in the nerves and hence, controls their bodily functions which become imperative in mastering the following limbs. Pranayama also increases hunger and decrease the byproducts that the body produces. Hence, the yogi is able to sit in meditation for longer times.

Also, according to Patanjali, “It weakens the darkness that blankets the knowledge. Practicing it increases the concentration and ability of the mind.” (Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, 2.52 & 2.53)

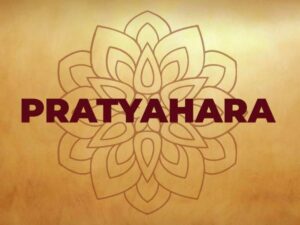

Pratyahara

The fifth limb of Yoga is Pratyahara or withdrawal of senses. It is the practice of forcefully constraining the senses from the material objects they desire. There are five senses in a human body that perceive and desire the pleasures of the material. They are ears (sound), skin (touch), eyes (form), tongue (taste), and nose (smell). Apart from these, there are three more internal senses: Mana (mind), Buddhi (intellect), and Ahankara (ego).

According to Patanjali, “When the senses do not feed on the contact of their respective objects, they take the form of pure consciousness. This is called Pratyahara.” (Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, 2.54)

To understand Pratyahara, we need to understand that the underlying truth behind all senses is consciousness. According to the Vedas, consciousness gave birth to Ahankara, Ahankara to Mana, Buddhi, and Akash (sky). Akash underwent changes (doped with impurities) to create air, air to fire, fire to water, and water to earth. Hence, the sky has the property only of sound, while air has the properties of touch and sound. Similarly, fire has the properties of form, touch, and sound; water has taste, form, touch, and sound, and earth has all five properties—smell, taste, form, touch, and sound.

The Result of Pratyahara

The thing to understand here is that the senses behave differently because of impurities or ill knowledge. At the root, they are pure consciousness. So, when you suppress their contact with their subjects, eventually, they start feeding on their root object, which is pure consciousness. Of course, it is easy, said than done, because the senses fight back. But with dedication, one can aim to feel no pain or pleasure in food, clothes, human contact, or any other luxuries. The yogi who has mastered Pratyahara devotes their actions in the service to the supreme soul that is pure consciousness—They consume the objects of the senses only to survive, and neither enjoys nor despises them.

Hence, Pratyahara becomes the most important skill which helps us to focus our attention inward, away from the distractions of the external world, and takes us to the next level in the Ashtanga Yoga.

Note:

The next three limbs of Yoga are significant as practicing them together is the best way to achieve salvation, as Patanjali has said. But I will not be writing about them in detail, as one needs to acquaint themselves with some knowledge of Hindu literature before they can understand these limbs. There is a lot of talk about faith, deities, and transcendental experiences in these parts, and if you do not practice or at least respect the faith, they may come as superstition, impractical, and even controversial to you.

However, I will write a brief introduction to Dharana, Dhyana, and Samadhi. For more information, you may read the original texts.

Dharana

The sixth limb of Yoga is Dharana. Some people translate both Dharana and Dhyana into meditation, but obviously, they are not the same. Dharana means ‘to hold’ or bind the attention to a single place, while Dhyana means to keep the mind concentrated on an object for a significant amount of time.

According to Patanjali, “To bind the consciousness in a place is Dharana.” (Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, 3.1)

Focusing Out of Body

While in an Asana, and doing Pranayama, a yogi has to focus on a point to get to the next limb that is Dhyana. This point can be inside or outside the body. The sages have advised a few places if you are focusing on the outside. One of these points is in the middle of the triangle created by your eyebrows, and the bridge (the part of nose between the eyes). Another point is if you keep your head straight, half close your eyes, and then look at the ground. It is neither too far nor too close. Also, you can look at a point on the ground with your chin placed on your chest and eyes half open. This point is closer than the previous.

Focusing Inside Body

If you choose to focus inside, you can focus on the point in your heart that is at the intersection of the ventricles (the size of a thumb), inside your brain (where amygdala is located), or on the Kundalini. For people who do not know where Kundalini is, the vertical distance between the root of the reproductive organ and the anus is 4 fingers wide. Inside the body, the point in the middle of the two is where Kundalini is located.

Whether or not you subscribe to the Hindu faith, with Dharana, your concentration and attention span will increase. It will also help in developing patience and inner peace. Post this, practice the limb of Dhyana or meditation.

Dhyana

Dhyana or meditation is the practice of keeping the concentration for a long time and with a definitive subject in mind.

Patanjali says, “At the place of Dharana, when the elements of consciousness become fused as one, it is called Dhyana.” (Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, 3.2)

Meditation is of different types. Even when you are not trying, you meditate. For example, when you lose yourself in a memory, you ignore the things you hear, see, or smell. We practice is consciously when we try to solve a problem. We visualize the problem, try to understand it through different perspectives, and so our senses become unified in the process—the problem at hand takes the form of our sight, sound, and so on. In fact, this is how creativity works. We are capable of analogies, metaphors, and comparisons because we can unify different things.

Meditation for a Yogi

A yogi practices the same meditation, but along with the other limbs, the results improve. Hence, with Dhyana, a yogi can unify the senses and all other elements of consciousness to become one with their soul. Not only do they constrain their senses from their objects, but the senses completely disappear. The physical senses still are present, and the yogi receives the external stimuli, but the brain does not process them. Hence, the yogi does not feel pleasure or pain, and the stimuli do not hinder the yogi’s Dhyana. When the yogi comes out of meditation, they can know those experiences as a memory.

Dhyana or meditation is vital if we want to gain knowledge. A spiritual seeker can meditate to achieve salvation, but even a person who wants worldly knowledge can practice it and see the effects themselves. After all, every knowledge leads to the same destination. After a yogi becomes a master of Dhyana, the possibility of the last limb of Yoga opens after which a person need not perform any actions.

Samadhi

The eighth and the last limb of Yoga is Samadhi. It is the state of enlightenment where the yogi achieves salvation while living.

According to Patanjali, “When Dhyana leads to the awareness of the nectar of its subject, and the meditator’s self-awareness disappears, it is called Samadhi.” (Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, 3.3)

By practicing all the previous steps correctly, the yogi arrives at the point where the material things do not exist for them anymore. Their senses disappear and they even leave the state of meditation. Meditation only happens when there is a meditator and a subject. But in the state of Samadhi, that difference vanishes, leaving the meditator unified with the subject. The soul of the yogi becomes one with the supreme soul and the yogi transcends to a plane of utter bliss and knowledge. This state knows no form, but only exists as the ultimate truth.

As I previously mentioned, you can achieve Samadhi by practicing any or all limbs of Yoga. However, depending on the practice you take, Samadhi varies too.

Types of Samadhi

Patanjali writes, “To cure the consciousness of impurities namely debate, thought, pleasure, and characterless-ness is called Sampragyat Samadhi. The other state of Samadhi (Asampragyat) is whose former state is the cessation of the senses, and in which the consciousness remains only in the metaphysical. While Videha—where the yogi in samadhi becomes one with the flow of the nature is the state called Bhava-Pratyaya” (Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, 1.17-1.19)

While the first five limbs of Yoga easily lead to Sampragyat Samadhi. The last three limbs work closer to achieve Asampragyat Samadhi, which the sages have described more difficult and of a higher form. The last and most difficult state to achieve is the Videha stage. At this stage, the yogi looks and acts like a normal person (they may even seem a little unpredictable, and out of their senses), but they remain free of any impurities and live in a continuous state of knowledge and bliss. There are scarce examples of people (like Dattatreya, Yagyavalkya, etc.) who have achieved this.

Stages of Samadhi

If the yogi masters the balance of Yoga, and nothing in the universe staggers their faith, only then can they achieve the last stage. When a yogi arrives at Samadhi, they become one with the universe, and hence gain the knowledge of the past, present, and future. They gain special skills with which they can know the difference between apparently the same objects, enter other’s consciousness, etc. Later, the yogi arrives at a state called Dharma-Megha. As the name suggests, in this state, Dharma rains continuously on the yogi, and the masked knowledge uncovers. Because of this continuous rain of knowledge, the yogi now cannot make errors. With unbound knowledge and free of all impurities, the consciousness becomes calm and free of all activities.

Ultimately, the yogi sees their own form (the difference between the seer, the object, and the vision disappears), and they even leave the skills behind. The knowledge of self and the others disappear, and the yogi loses the sense of awareness. In such a state, the yogi becomes action less—although they perform their duties, any of their actions do not disturb the world and hence they become free of sins and virtues.

Thus, Samadhi, being the ultimate aim of a yogi, liberates them from all actions, bounds, and impurities.

Fun fact:

King Janaka of Mithila lives in a Videha state. In fact, all successors of Mithila are named Janaka because they live in the same state. Using this knowledge, King Janaka, although maintaining his kingdom (living in luxury, fighting wars, etc.), remains bodyless and actionless.

Conclusion

The Yoga sutras of Patanjali are a valuable resource for anyone looking to improve their physical, mental, and spiritual health. The teachings in these texts can help you learn how to relax your body and mind, increase your concentration and sense of well-being, and achieve your goals in life with greater ease.

These texts are not mere tricks to fool your mind into a temporary relaxation or happiness. They lead the yogi to a result, where they attain unbound knowledge, bliss, and even salvation. The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali are an inclusive text that describes the problems one could face in practicing Yoga, the solutions to these problems, the eight limbs of Yoga, and the results. It gives a deep insight into the philosophy of life and spirituality and is comprehensive for anyone who wants to delve into the life of hermitage. The practice is as challenging and easy as you want to make it. You can try one limb or try them all simultaneously. Similarly, you can choose to practice the Patanjali’s sutras alone or club them with other practices of Yoga, and meditation to see what works best for you.

However, I would strongly recommend that you read the literature at least once and see for yourself if it works.

Read more on the practice of Mindful Meditation, a complete guide and how-to.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is Yoga safe?

Yoga is quite safe, and there is little evidence that it is harmful. However, as with any exercise or practice, always consult your health practitioner before beginning a Yoga routine if you are pregnant or have any medical conditions.

What should I do if I feel dizzy or lightheaded during my practice?

The sages have described three categories of results while practicing Yoga. An inferior category is when the Yogi shivers and feels uncomfortable. The mediocre category is when the Yogi sweats while practicing. If this happens, stop practicing and move a step back. Master the previous steps and only then move forward. The optimal result is when it feels like the body has become light and a feeling of ascending upwards comes.

If you experience any other symptoms such as chest pain, dizziness, or shortness of breath, please consult your health practitioner immediately.

How can I use Yoga sutras to help achieve my goals?

While the ultimate purpose to practice Yoga should always be detachment from the material world and salvation, a yogi learns several skills in the practice. Yoga takes a long time to master, and so, before you achieve salvation, you can use these skills to achieve momentary goals in life.

One of the key benefits of practicing this ancient art is removing the adverse effects of life. With Yoga, you can overcome psychological problems, straighten your routine, develop healthy habits and more.

Also, meditation and Pranayama help in improving thinking skills, attention span, memory, and creativity, which can help you in your day-to-day life.

Last, Yoga empowers its practitioner with knowledge of seeing the world under a different light—understanding things as they are. You can use this knowledge in your field of profession to develop ideas and workflows that can help you as well as others.